When it came time to remodel the facade of the headquarters building of the Hanwha Corp., a renewable technology firm based in Seoul, South Korea, the design focused on two aspects: the amount of sunlight striking each side of the building and the integration of the corporation’s own photovoltaic panels into the new building envelope. The international engineering firm Arup, the project’s sustainability and facade consultant, worked closely with the Dutch architecture firm UNStudio on the new system, which features 54 types of facade modules arranged in 239 configurations, according to Vincent Cheng, Ph.D., an Arup fellow and the firm’s director of sustainability in East Asia.

The building is a roughly 60,000 sq m structure that rises 29 levels above grade on a site next to Seoul’s Cheonggyecheon recreational canal. Constructed in the 1980s, the building featured a conventional window wall system attached to composite slabs supported on H beams. But in recent years this facade had become “somewhat dated, both in terms of aesthetics and environmental performance,” notes Tony Lam, Ph.D., Arup’s associate director of sustainability and East Asia building performance and systems leader. Consequently, Hanwha “aimed to remodel its headquarters to reflect its position as an advanced, leading renewable technology firm,” explains Lam.

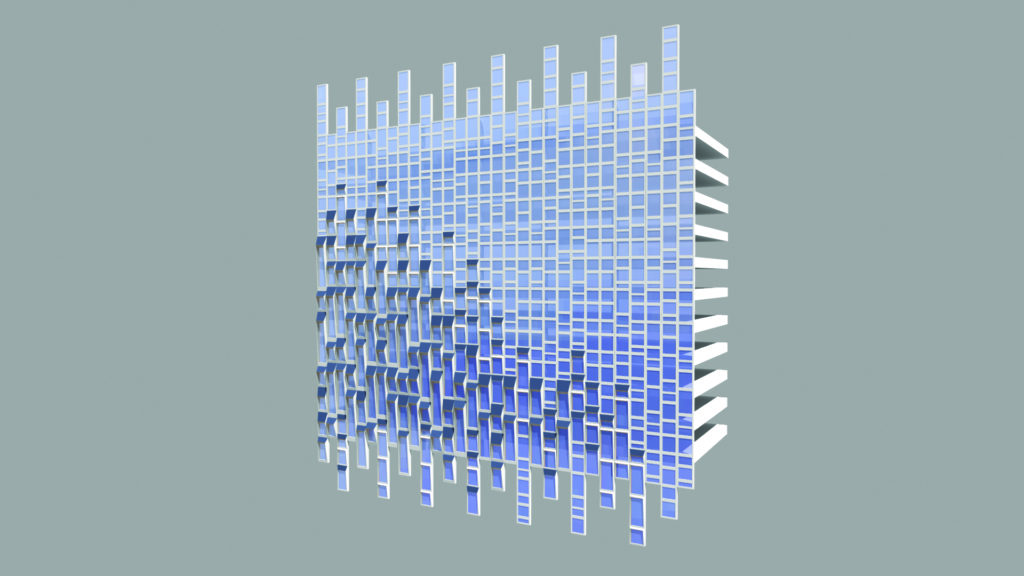

The design and distribution of the new facade modules, which feature aluminum mullions and transoms, were based on the amount of solar irradiation and daylight received on different sides and sections of the building. Thus, on the south side of the structure, where the solar irradiation can be the heaviest, the modules protrude farther out to provide extra shading. On the less sunny north side, the modules are slightly recessed to allow more light into the interior spaces of the building. The facade areas encountering greater solar irradiation were designated as “eye” zones, and the areas with less irradiation were designated as “regular” zones, Lam adds.

In addition to the varying parametric design of the modules, the facade also integrates 301 Hanwha photovoltaic panels into the new building envelope; another 370 panels were installed on the roof. The PV system is designed to generate 100 kW of electrical capacity, equaling 3 percent of the building’s energy consumption.

The overall system is described as an integrated responsive facade designed to perform optimally in terms of energy consumption and power generation, glare, thermal comfort, and other factors under the full range of environmental conditions it may face throughout the day and season. Aesthetically, the building’s appearance will also change continually based on the weather and time of day because of the architectural shading features, Lam notes.

During the retrofit, the original facade was disassembled and replaced with the new system, which was secured to the existing structure through support brackets welded to the outer surface of the original H beams.

To develop the new integrated responsive facade system, Arup relied heavily on computer simulations “to holistically optimize the proposed design whilst maintaining the original architectural intent,” Lam says. These simulations included a solar radiation model that helped eliminate PV panels that would be too heavily shaded; a glare study designed to eliminate PV panels that might have high visual impact on surrounding buildings; a shadowing analysis to optimize the wiring configuration of the system, which Lam said helped determine that the panels should be connected vertically to maximize efficiency; an estimation of the PV panel output; a thermal comfort simulation; an energy consumption analysis; a daylighting analysis; a glazing optimization study; and a life-cycle analysis. The design team also used a Grasshopper optimization algorithm — created by Robert McNeel & Associates — to help determine the patterns of the modular facade elements.

The modules were fabricated off-site and installed easily and quickly with minimal impact to air quality or noise for the building’s roughly 6,500 occupants, says Lam. This was critical to the project’s success because the building remained occupied for the majority of the construction phase, which lasted from 2017 to late 2019. Three floors at a time were vacated as the retrofit work proceeded up the building; the other floors remained fully occupied and in operation until it was time to work on their parts of the facade.

The new facade system has significantly cut the building’s energy consumption, reducing the energy needed to heat a typical floor by 36 percent and reducing the energy to illuminate a typical floor by more than 26 percent, Cheng adds. Hanwha has extended the life of its existing headquarters by an estimated 20 years, he notes. Furthermore, an embodied carbon analysis indicated that by replacing just the facade — rather than constructing a new building — the project reduced the potential embodied carbon emissions by 71 percent. Because the Hanwha building’s overall structure and original mechanical systems were still in good condition,” Cheng concludes, “replacing the facade was the most sustainable option.”

This article first appeared in the December 2020 issue of Civil Engineering as “New Modular Facade Adorns Renewable Technology Firm’s HQ.”