The 2019 ASCE Education Summit, held in Dallas last May, included a mission statement of sorts as its subtitle: “Mapping the Future of Civil Engineering Education.”

A year later, ASCE has released that map.

The full report of summit findings is available as a free download on the ASCE website.

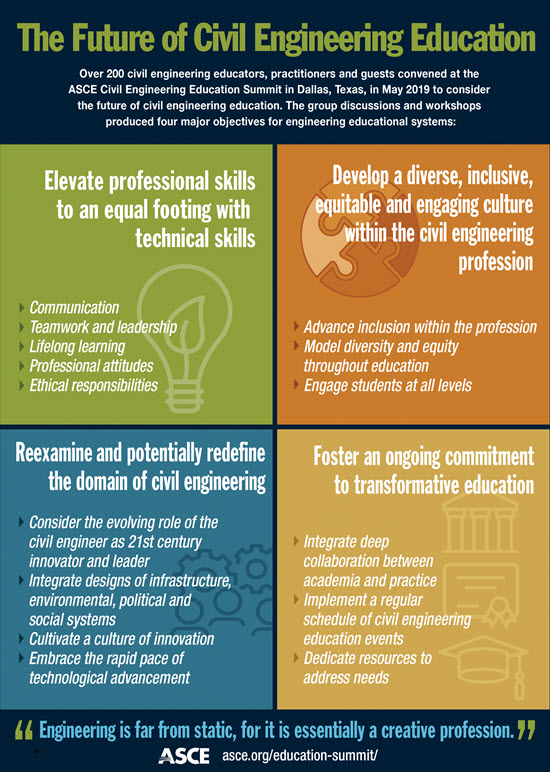

Included in the report are four key recommendations that provide a structure of aspirations for civil engineering education:

• Elevate professional skills to an equal footing with technical skills.

• Develop a diverse, inclusive, equitable and engaging culture within the civil engineering profession.

• Develop a diverse, inclusive, equitable and engaging culture within the civil engineering profession.

• Reexamine and potentially redefine the domain of civil engineering.

• Foster an ongoing commitment to transformative education.

“We need to, as educators, incorporate this into the curriculum but also articulate why the students need this knowledge, why these changes are happening and why they should continue to happen into the future,” said Audra Morse, Ph.D., P.E., F.ASCE, chair of the civil and environmental engineering department at Michigan Tech.

“I really like that the report starts out by saying ‘Engineering is not static.’ The profession is not static. Their careers will not be static. So the knowledge that they need is not going to be static.”

More than 200 civil engineering educators, practitioners and guests convened at the ASCE Civil Engineering Education Summit in Dallas, May 2019, for group discussions and workshops surrounding the future of civil engineering education. Now that the report has been released, a newly formed Civil Engineering Education Summit working group is refining and further developing the objectives outlined in the report into actions for ASCE to take.

“It gives people time to meet with industry, to meet with academia, and say, ‘OK, what do we see? Let’s look beyond tomorrow. Let’s look well into the future. What do we see as trends? What do we see as the needs both from industry as well as what students are demanding?’” said Scott Hamilton, Ph.D., P.E., F.ASCE, chair of ASCE’s Committee on Education and chair of the civil and mechanical engineering department at York College of Pennsylvania.

“Because the majority of civil engineering majors are going to go out and practice, and being able to prepare them is job number one for us.”

It was the first such ASCE conference since 1995’s Civil Engineering Education Conference. And a quarter-century is a long time in any industry, but the last particular quarter-century feels particularly momentous in terms of change in this particular industry.

The summit report’s recommended objective to potentially redefine the domain of civil engineering feels especially necessary and powerful, Hamilton and Morse agreed.

“So many things have happened since 1995, new things that were never even considered civil engineering then and now are,” Hamilton said. “We’re looking at the role of data analytics now. No one was really doing that then. We know AI is coming forward. How is that going to impact buildings? The whole idea of the Internet of Things. How do we integrate all of this?

“It changes the way we can operate and should operate. And it means that as a profession we have to keep up.”

COVID-19 has changed the world even further in the 13 months since the 2019 Education Summit. Morse said she thinks the current events of 2020 have only reinforced the summit findings.

“Our world has been shaken up, and there’s good that can come from that shakeup,” Morse said. “It will be interesting to see how we rethink infrastructure, how we move people, how we plan things like stadiums.

“I think the civil engineering profession has to respond and learn and do better. Which is really what this document is all about.”

I think you are making a mistake by involving only educators in the discussion. Most university professors have never worked anywhere to get real life practical engineering experience, so do not completely understand the needs of practitioners. You should also involve leaders of the construction, user agency professionals, and consulting engineering fields of practice. They are the ones that best understand the profession’s needs. There once was a geotechnical engineering professor at UBC in Vancouver, Canada, who took a sabbatical leave to work for a consulting engineering firm in Calgary, Alberta, CA. At the end of the year’s sabbatical of working in real life, they asked him what he thought of it. His response was: “I will have to completely redo my lectures, because I never realized that I was not telling the students what they really needed to know for real life practice of the profession of Civil Engineering”. I only have 50 years of experience on 6 continents, but that is my opinion from my experience.

Mr. Richards: Absolutely agree!! We invited practitioners to join the Education Summit (and a small number did), and have excellent representation from the practitioner community on the Summit Working Group. We look forward to even greater practitioner participation in the future!

I agree with Donald’s sentiment. One of the most valuable things for engineers to learn is how to apply what they have learned in the real world. As such, engineering students should be educated in the fundamental principles of the materials taught. We need to avoid producing engineers who can only solve textbook problems, but cannot see how to apply engineering principals to real problems. While it is good to learn about codes and standards; these things change over time, while the underlying principles do not. If we want to be valued as professionals, we cannot be cookbook engineers. Soon AI will be able to do that. If we do not teach practical application, there will be no one capable of managing what an AI does or deciding which approach to use and the value of engineers will decline. Valuable engineering relies on insight and creativity; two things that could use a good deal more emphasis in engineering education.

Mr. Byle: Thank you – you are spot-on with your comments. One of the key recommendations arising from the Summit is to encourage greater collaboration between academia and professional practice. We encourage you and your colleagues in practice to seek out opportunities to become involved with your local colleges and universities – for example, serving on Industrial Advisory Boards, judging student design projects, or serving as Practitioner Advisers for student ASCE chapters. We need your help!

Universities seem to be more into “education” than “graduation.” Tuition increases have outpaced the general economy, yet classes at many universities, especially at engineering schools, are either unavailable or packed beyond the optimum level for effective transfer of knowledge. With student tuition dollars being directed to one-sided, progressive/liberal political indoctrination initiatives, too little is directed at efficiently and effectively educating the future civil engineer.

ASCE has ignored the erosion of the esteem of the engineer in society to the point where many think of engineers as the proverbial “nerd”, which makes the thought of four tough years of college work unappealing to many potential engineers, especially when they can pursue less demanding course work and end up making about the same money or more at graduation. Further, in terms of inflation adjusted income, civil engineer salaries have degraded over the last 30 years leaving many other fields much more attractive to college entrants. In too many cases, graduates of civil engineering programs end up going into careers unrelated to civil engineering.

In too many ways, civil engineers are our own worst enemies due to lack of professionalism. Bidding of projects is rampant. So called “professional” engineers in government positions gleefully set a bidding atmosphere with each RFP they release, and often drive proposed hours down to below having sufficient hours to effectively think through and execute the project the way engineers should…but desperate for work, there are engineers that will do anything to get a job, and that includes under estimating and working for free just to have work. Engineers are literally destroying from within what was once a profession.

ASCE has a role, and it needs to start by improving the conditions in the civil engineering profession. And that does not start with the education curriculum. The education curriculum will need to be addressed, but not until the profession can be re-established to just that, a profession and not a trade.

I agree with the previous responses. Also, adding professional skills to the curriculum is a nice idea but for structural engineering it cannot be at the expense of technical knowledge. A great public speaker who cannot design safe structures is dangerous. A number of structural engineers are content to be very good engineers and not go into management or deal with the public. They provide an important roll in our firms.

Having attended a university that required engineers to co-op (alternate quarters or semesters of work experience with school) and having employed co-op students in my structural engineering firm, I feel the work experience is as valuable as any course work. Upon graduation, co-op students hit the ground running and are productive immediately. Donald’s example would not be as great of issue because the students are seeing how things are done while at their work sessions. Hopefully, they would be reporting this back to the professor.

I took a public speaking class in college and it was worthless. Joining Toastmasters is a much more effective way to develop public speaking skills. Also, participating in organizations like Jaycees provides a good way for young people to develop their professional and managerial skills. Some firms require their professional employees to volunteer on the boards of charitable and civic organizations to help develop their professional skills.

In summary, I think there are better ways of learning many professional skills other than in college, especially if the technical education is diluted in order to make room for the “professional” classes and all engineering schools should require co-op experience even though it extends a 4 your program to 5 years.

Mr. Schaefer (and also Mr. Labit): Indeed, the various constraints on units required for graduation is one of the significant challenges to delivering a civil engineering degree program. There is pressure on many fronts to continue to reduce units, including many State Legislatures. Increasing the value of professional skills, however, does not necessarily imply “taking more courses” (which, in a zero-sum environment, would possibly mean reducing the ‘technical’ content of a degree program). Many programs are seeing success in integrating professional skills within the context of existing design courses – areas such as communications, ethics, social justice, sustainability, and others. As we continue to move forward, these same challenges will continue, and possibly grow. This is one of the factors which led to the selection of the Summit theme of “Empowered to Innovate” — seeking ways in which we can be more innovative and creative in developing students’ knowledge, skills, and abilities AND inculcating a culture of innovation within our graduates and our profession.

As a retired person I look back on the things that made my career path what it was. The first thing that comes to mind in the realm of education was my 150 hour BS, not today’s 128 or so. My education foundation prepared me for engineering a wide variety of matters, whether electrical, mechanical, structural, or civil in nature. I always worked for the owner and hired engineers as necessary to supplement the company’s needs. During my school time I always asked the question: “How can this be applied in practice.” When no one else could solve a technical problem, the boss called me to get things in order. Creativity, supported by a firm technical foundation, was my way to get things done. Early in my career I did take the Toastmaster course, and two masters degrees to supplement my base education. We need both types of engineers, the technocrats and the managers. Some people are better suited for one tract or than another. Do not water down the technical aspect of education because one can get the other none-technical items from other sources.

Until the principles of physics of Physics (Newton’s Laws, water runs downhill, etc.) change I would oppose changing the teaching of Civil Engineering! All of those immeasurables that you define as “Professional Skills”, will come out during one’s early years in the profession and can’t be readily taught in the engineering classroom, anyway. Those develop best in Life’s classrooms. The second bullet point regarding diversity and inclusion are sad for me to read. I graduated nearly 50 years ago from a top Engineering institution with many African-American Engineers walking across the same stage as I did, and they deserved that as much as I did. As far as I know they took the advantage of the great education we both worked for, and made careers every bit as successful as mine. If they were able to be truthful about it they would resent a move that acknowledged some disability to learn Civil Engineering as it had been taught and evolved on a scientific basis, not some BS anthropology theories. Please forget this roadmap, because where it will take you, my profession does not want to go.