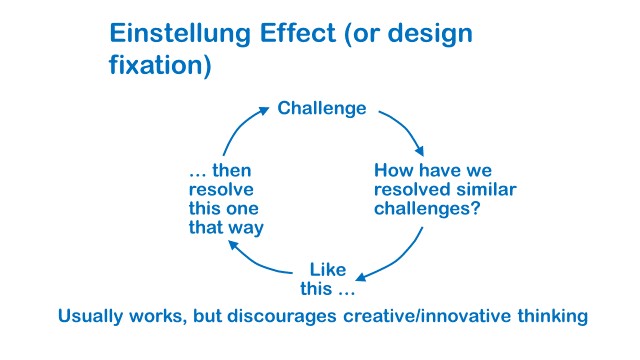

The Einstellung Effect – where the German word means “approach” or “way of doing something” – refers to trying to resolve an issue, problem, or opportunity only by using approaches that have worked in similar situations, rather than looking at each new situation on its own terms. This narrow, habitual, and left-brain dominated tendency, which is illustrated below, inhibits creativity and innovation.

Another term for this creativity-innovation barrier is “design fixation,” which may be defined as unintentionally applying a set of ideas or concepts that limit the range of possibilities of the design. The ominous word is “unintentionally” because it reminds us that we may unknowingly or habitually rule out a fresh perspective.

Although we may welcome a new challenge and commit to resolving it, we are often unwittingly locked into past solutions. Call it what you want – Einstellung Effect or designfixation – this predisposition to familiarity may prevent consideration of much better and more creative and innovative approaches. As noted by change thinker John C. Maxwell, “The difficulty lays not so much in developing new ideas as in escaping from the old ones.”

Design fixation as an approach – a traditional, time-proven engineering way of doing things – is sound. It has resulted in untold numbers of successful engineered systems, facilities, structures, products, and processes and has resolved many nontechnical challenges.

Design fixation as an approach – a traditional, time-proven engineering way of doing things – is sound. It has resulted in untold numbers of successful engineered systems, facilities, structures, products, and processes and has resolved many nontechnical challenges.

So why the concern? Why question it? Why mess with success? Because we may find great value in at least exploring, in parallel to the tried and true, some fundamentally new approaches. Rehashing old solutions can leave us shortchanged.

What Can We Do?

Assume we want to avoid the Enstellung Effect because it typically causes us to miss out on personal and organization benefits often associated with creative and innovative approaches to resolving technical and nontechnical challenges. We don’t want to thoughtlessly get stung by Einstellung.

Then, the next time we want to resolve an issue, problem, or opportunity, let’s encourage ourselves and others to take a time out from the usual approach. Instead, first thoroughly define the challenge and then seek, perhaps in parallel with what has worked in the past, a creative and innovative resolution.

Then, the next time we want to resolve an issue, problem, or opportunity, let’s encourage ourselves and others to take a time out from the usual approach. Instead, first thoroughly define the challenge and then seek, perhaps in parallel with what has worked in the past, a creative and innovative resolution.

Apply collaborative, whole-brain tools such as Borrowing Brilliance, Mind Mapping, Fishbone Diagramming, Biomimicry, Six Thinking Caps, TRIZ, and What If, or use whatever might work for you, such as traditional brainstorming – see 20 Methods to Stimulate Creative/Innovative Thinking.

The risk is low (we can, if we have to, usually fall back on resolving the challenge the way we always did) and the potential payoff is high – including the satisfaction of doing what has never been done before.

Consider some examples of what happens when engineers take a whole-brain, creative/innovative approach:

• In 1905, engineer John F. Stevens took over the struggling construction of the Panama Canal and saw this canal construction as a railroad project, not as another excavation project. His atypical approach rescued the effort and sent it on to completion in 1914.

• Eiji Nakatsu was chief engineer of the West Japan Railway Corporation in the 1990s. That system’s high-speed trains caused loud, unacceptable booms as they exited tunnels. As the train sets moved through the tunnels, the snub-nosed first units compressed the air, which rapidly and loudly expanded at the tunnel exit. Nakatsu and his staff approached the problem in a very atypical fashion. They conducted laboratory experiments using different shapes for the lead units with the shapes being inspired by bird beaks. The shape of the Kingfisher’s beak solved the problem as shown here.

• About two million newly born babies die each year, mostly in developing countries, because the infants lack a consistent heat source. The conventional solution is to send modern incubators, as used in American hospitals. They cost $40,000, require careful maintenance, fail after a few years, and the parts and skills needed to fix them are not available locally. The usual solution is to find the funds needed to purchase new incubators and send them overseas. However, engineer Timothy Prestero went in a different direction by leading the design of an incubator that cost less and could be maintained and repaired locally. How? His baby incubator is assembled from many locally available automobile and motorcycle parts, such as a sealed beam headlight to supply heat, an automobile dashboard fan to circulate air, and a motorcycle battery to provide power during an outage or when the incubator and baby are transported.

Perhaps my “avoid the Einstellung Effect” advice sounds easy, obvious. It is easy to understand but not easy to do because most of us are understandably governed by habit and tempted to take the easy way.

Let’s not thoughtlessly go down those paths when another one, more satisfying to us and others, may appear. Let’s proactively look for it.

Stu Walesh, Ph.D., P.E., Dist.M.ASCE, is the author of Introduction to Creativity and Innovation for Engineers, which was published early this year by Pearson.

I like topic, there is one more thing that the effect is destroying. It destroys professionalism and competition in innovation. Now a days many product based companies has so embraced the effect that they only depend on managers and production people to run their business while innovative and technical people are just small portion of the work force sometimes their work are just one off thing in pay and work duration. Yet what was produced by creative thinking is the one that the companies profiting on.