As civil engineers, many times we find ourselves leading talented multidisciplined teams. This was certainly my experience when I worked on billion-dollar freeway programs that included all the engineering disciplines – along with historians, community engagement specialists, threatened and endangered species experts, and more. I love leading experts who are passionate about their area of expertise.

But nothing has challenged me like the current project to manufacture personal protective equipment in Guatemala during the COVID-19 response. It is a joint program between Engineers Without Borders USA and the Guatemala Rotary. (I shared more details in a recent ASCE Plot Points podcast.)

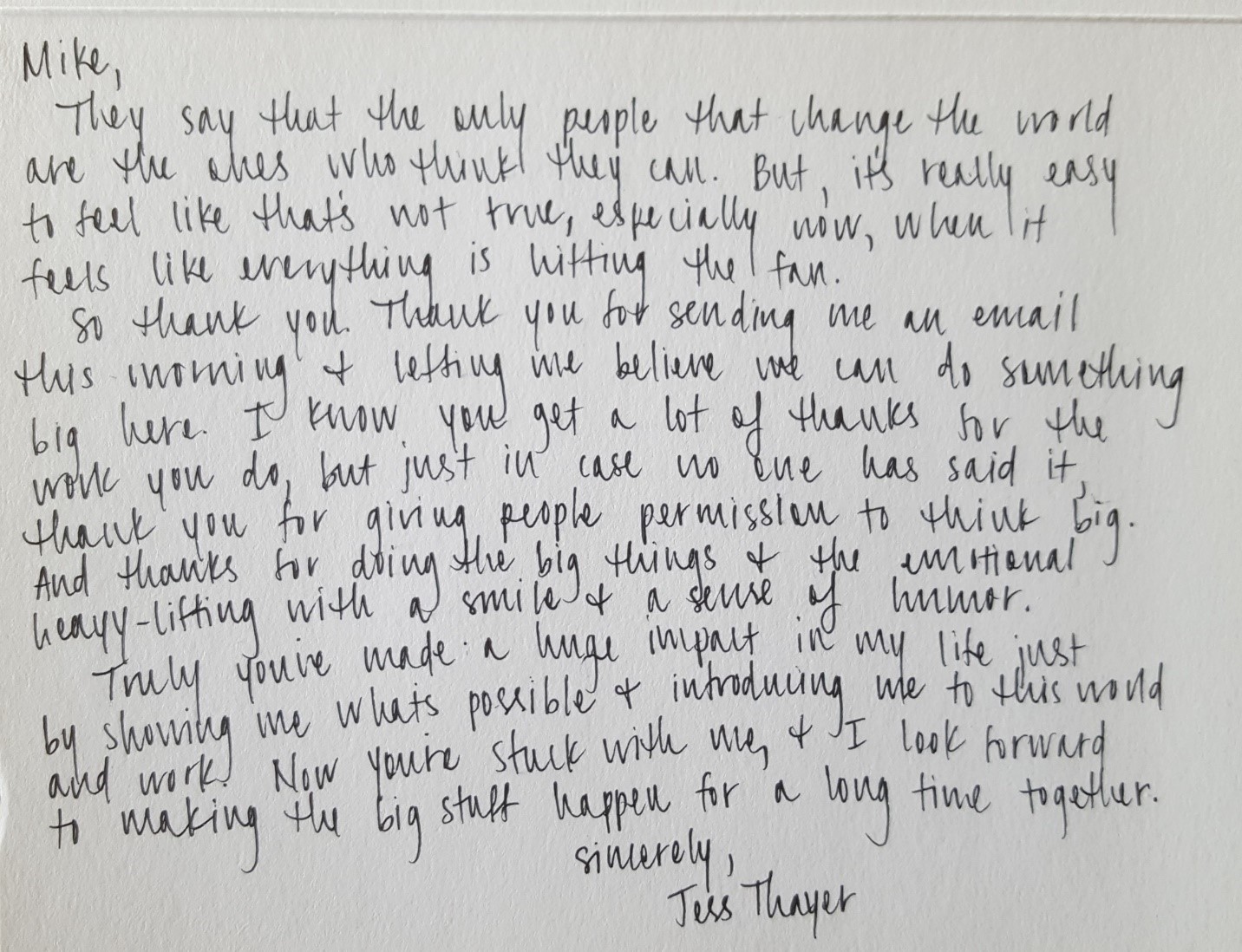

Two years ago, I met Jessica Thayer at a conference. I had just finished giving my presentation on disaster response and she introduced herself. Jess greeted me with a firm handshake and a big smile. She had a big idea that was bursting to get out of her. She wanted to engage in disaster relief using her skills as a biomedical engineer to complement our civil engineering projects.

Two years ago, I met Jessica Thayer at a conference. I had just finished giving my presentation on disaster response and she introduced herself. Jess greeted me with a firm handshake and a big smile. She had a big idea that was bursting to get out of her. She wanted to engage in disaster relief using her skills as a biomedical engineer to complement our civil engineering projects.

“Civil engineering and healthcare need to partner beyond buildings and WASH,” she said. “We need to go farther.”

For over a decade, EWB-USA has worked to improve water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) in clinics and hospitals around the globe. It is a daunting task. Nearly 2 billion people lack access to a health care facility that has adequate WASH. I find this impossible to comprehend. But it is real, and I have seen it far too many times. Jess’s idea of including biomedical engineering work into EWB-USA’s healthcare facilities projects was intimidating but would be very impactful.

“I have no idea exactly how we will do this,” she said, “but I bet we can figure it out together. If you’re in, so am I.”

She held up her pinky and I linked my own to it, solidifying our promise to one another.

Fast-forward to early February. EWB-USA and Rotary Guatemala were kicking off a program to help hospitals prepare for the additional caseload by increasing the water supply and storage at the facilities. We worked with hospitals to design and build triage areas and larger waiting rooms in anticipation of the increased caseload.

But we also heard the hospitals loud and clear: “Our staff needs PPE!”

We knew other countries were spiraling out of control with COVID-19 cases. Guatemalan healthcare workers were scared to go to work because of the lack of PPE due to broken supply chains, fearing for their health and that of their families. Patients were losing hope and not seeking help at hospitals when they were sick out of concerns over the virus and the lack of PPE protection.

I was on Marquette University’s campus when Jess stopped me in the hall. She was working as a graduate student with a team to develop PPE for health care workers in the United States. She posed a “crazy idea” to me.

“Why not try to do the same in Guatemala?” she said with a challenging smile.

I agreed to fold the work into the program and mentor her in the process. Through numerous video calls from our homes in Wisconsin, we scoped out the project with the Guatemalan Rotarians and EWB-USA’s in-country staff.

Jessica dug into her tasks with unwavering energy as the civil work continued. She found Rebecca Alcock, a biomedical engineering doctoral student at UW Madison, to co-lead the effort. Rebecca is a ball of energy wrapped in a shell of calm and soothing kindness. She had worked as an EWB-USA fellow in Guatemala for one summer and was familiar with the culture and conditions.

Jess and Becca threw themselves into the work with vigor. They recruited medical doctors from Guatemala to advise them on appropriate cultural solutions, and biomedical engineers with industry experience who helped coach the Guatemalan Rotarians on how to recruit partners to manufacture the PPE products requested by the hospitals. The duo made countless video calls with manufacturers and suppliers to help select the right materials and processes. Jess and Becca also expanded their network, collaborating with other universities in the United States and Guatemala to round out their team.

In only five weeks, the team of a dozen biomedical volunteers developed, prototyped, approved, produced and shipped hundreds of thousands of PPE to the hospitals before the anticipated peak of caseloads arrived. The video messages from the emotional doctors at the hospitals thanking us for the support was overwhelming and made all the long nights worthwhile.

Good leaders learn that they work for those they lead, not the other way around. Our job is to remove barriers, provide resources and many times just provide encouragement to our hardworking teams.

As the saying goes, “Sometimes you need to lead, follow or get out of the way.” Clearly, with these two determined young engineers, my mission was the last.

COVID-19 has been a stressful crisis for us all, but let’s not forget that even in moments of crisis, mentoring opportunities abound and are so rewarding. Learn more about ASCE’s mentoring program, Mentor Match, and consider signing up today.

“Engineering With Heart” is a series of articles by Michael Paddock for ASCE News. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of EWB-USA.

Paddock, P.E., P.S., M.ASCE, a 30-year member of ASCE, is a licensed civil engineer and surveyor. His professional career was spent managing teams of over 100 engineers designing infrastructure projects over $1 billion, and he was the youngest-ever recipient of Wisconsin’s “Engineer of the Year” award.

After a near-death cancer experience, he was motivated to begin a pro bono engineering career that has delivered projects with Engineers Without Borders USA, Rotary, Bridges to Prosperity and other nonprofits on five continents over the last 20 years.

Paddock’s new book, “Bridging Barriers,” launches June 24. Learn more about how you can order it at www.bridgingbarriers.com.

Mike, your enduring commitment to helping others us very much an inspiration to former co-workers like me. I have retired and my voluteering has all been local.