October marks the anniversary of the George Washington Bridge, which was officially opened to the public Oct. 25, 1931. At its opening, the bridge surpassed the Ambassador Bridge in Detroit for the title of longest main span in the world.

Spanning the river to link New York City and New Jersey had challenged planners and engineers for decades. In 1888, Gustav Lindenthal proposed a suspension bridge at 23rd Street that would carry six railroad tracks. During the following years, arch and cantilever designs were also proposed and subsequently rejected.

Although Lindenthal’s suspension bridge plans were approved by the War Department, the economic depression of 1893 hindered financing of a bridge. Plans for a Hudson River crossing were revived in 1906 with the Interstate Bridge Commission looking at a bridge at 59th Street, but the commission ultimately opted for an underwater crossing.

The North River Bridge Company developed another proposal by Lindenthal for a large Hudson River suspension bridge at 57th Street in Manhattan. This grand design would have been built at a cost of $200 million to carry 20 highway lanes on the upper level and 12 railroad tracks on the lower level, all supported by eyebar chains. However, neither the city nor the railroads were supportive of this design.

In 1921, a bill was introduced in the New Jersey Senate to create a corporation with the authority to construct a pontoon bridge between Alpine, NJ, and Yonkers, NY, as a temporary crossing measure. The pontoon-bridge plan was dropped but New York Governor Alfred E. Smith Jr. and New Jersey Governor George S. Silzer urged the newly-created Port Authority of New York to construct a Hudson River crossing.

Preliminary designs for a bridge began in July 1925, and test borings were made at 178th Street. The site was chosen as the most desirable because of its topography and for its potential connections to adjacent roadways. The Port Authority of New York chief engineer, Othmar H. Amman, proposed a crossing near the northern tip of Manhattan where land prices were lower and the cliffs on both sides of the Hudson would lift the bridge over ship traffic.

The George Washington Bridge was the first of several major long-span bridges that Ammann designed in New York City. The design included a 3,500-foot center span suspended between two 570-foot steel towers to carry two levels of bridge deck. When construction started the estimated cost of the bridge was $75 million.

Ammann’s design applied the revolutionary deflection theory, which relates cable stiffness to deck load. Deflection theory premised that the greater the dead load supported by the cable, the less would be the effect of live load on the deck. Ammann concluded that under a great enough load, extrapolating deflection theory would result in cable stiffness mitigating motion of the deck and almost no stiffness would be needed in the deck itself. This theory, which does not account for wind loads, was taken to its catastrophic limit in 1940 with the Tacoma Narrows Bridge failure.

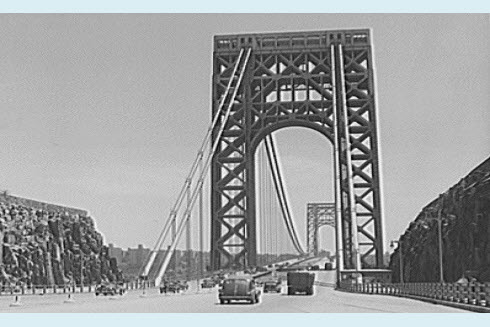

The world’s largest cofferdams were constructed to excavate 80 feet below the water level to create the foundations for the New Jersey tower. The two towers consist of 43,070 tons of steelwork held together by more than a million rivets. The original design for the towers of the bridge called for them to be encased in concrete and granite. However, cost-cutting measures taken during the Great Depression to keep the construction cost at $60 million postponed architect Cass Gilbert’s plan to encase the bridge’s towers.

After completing the towers, workers strung the main cables over the towers from both sides of the shore. Work on the steel cables began on July 14, 1929, and the final wire was spun on Aug. 7, 1930. The connections used 107,000 miles of wire fabricated by John A. Roebling’s Sons Company, more than four times the combined amount used in the seven largest suspension bridges of the time. Each of the four main cables is comprised of 26,474 pencil-thin wires and is a yard in diameter. The New York anchorage, into which the main cables are anchored, consists of 110,000 cubic yards of concrete and weighs 260,000 tons. The anchorage on the New Jersey side is the Hudson Palisades, comprised of the extremely hard and tough diabase rock that is commercially, but incorrectly, known as black granite.

With the cables strung, workers then hung steel suspenders from the cables, which would support the roadway. The last step was to build the roadway and hang it from the suspenders. Workers built the six-lane road deck in sections foot by foot, out from the shores, hanging it from the steel suspenders as they went. They carried the pieces to the construction site by rail, hauled them into the river by boat, and then hoisted them into place by crane.

The bridge was dedicated Oct. 24, 1931, eight months ahead of schedule, and opened to traffic the following day. New York Gov. Franklin D. Roosevelt dedicated the bridge, declaring, “This will be a highly successful enterprise. The great prosperity of the Holland Tunnel and the financial success of other bridges recently opened in this region have proven that not even the hardest times can lessen the tremendous volume of trade and traffic in the greatest of port districts.”

The efficiency exhibited by the Port Authority of New York in the design and construction of the George Washington Bridge impressed Roosevelt, who used it as a model in creating the Tennessee Valley Authority and other such entities after he became president.

Originally known as the Hudson River Bridge and the Fort Washington-Fort Lee Suspension Bridge, the bridge was officially named the George Washington Bridge by the Port Authority of New York, April 23, 1931. The bridge is near the sites of Fort Washington on the New York side and Fort Lee in New Jersey, which were fortified positions used by General Washington and his American forces in his unsuccessful attempt to deter the British.

During the first full year of operation in 1932, more than 5.5 million vehicles used the original six-lane roadway. As traffic demand increased, additional construction became necessary. The two center lanes of the bridge, which had been left unpaved in the original construction, were opened to traffic in 1946, increasing capacity of the bridge by one-third.

In August 1962, the bridge capacity was increased by another 75 percent as six lanes of the lower roadway deck opened, which the New York Times called, “a masterpiece of traffic engineering,” and other observers referred to it as the Martha Washington. With its 14 lanes of traffic and more than 100 million vehicles per year, the George Washington Bridge is now one of the busiest bridges in the world.

The George Washington Bridge is considered by many to be an aesthetically elegant work of structural art. Although the scale of the bridge was great, Amman’s application of deflection theory in the design made for a delicate, slender profile using horizontal plate girders in the roadway in lieu of vertical trusses.

Having gained public acceptance, the exposed steel towers, with their distinctive bracing, have become one of the bridge’s most identifiable characteristics. In 1947, French architect Le Corbusier called the George Washington Bridge the most beautiful bridge in the world.

“Made of cables and steel beams, it gleams in the sky like a reversed arch. It is blessed. It is the only seat of grace in the disordered city,” Le Corbusier said. “It is painted an aluminum color and, between water and sky, you see nothing but the bent cord supported by two steel towers. When your car moves up the ramp the two towers rise so high that it brings you happiness; their structure is so pure, so resolute, so regular that here, finally, steel architecture seems to laugh.

“The car reaches an unexpectedly wide apron; the second tower is very far away; innumerable vertical cables, gleaming against the sky, are suspended from the magisterial curve which swings down and then up. The rose-colored towers of New York appear, a vision whose harshness is mitigated by distance.”

The George Washington Bridge was designated as a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Civil Engineers, Oct. 24, 1981, the 50th anniversary of the bridge’s dedication ceremony.